The 7-Eleven Effect: Creative Pauses Reveal Hidden Patterns

Key Takeaways:

Deliberate creative pauses can dramatically enhance problem-solving by revealing cross-domain patterns that aren’t visible during intensive focus.

- Changing your environment through deliberate breaks creates mental space for new connections to form, often leading to breakthrough insights.

- The creative process benefits from lateral thinking approaches that break away from vertical, sequential reasoning.

- Structured frameworks like the Six Thinking Hats provide organization for divergent thinking, helping to capture insights from multiple perspectives.

- Pattern recognition across seemingly unrelated domains (like retail store design and blockchain implementation) can reveal powerful system-level solutions.

- Understanding your cognitive profile can help you design creativity techniques that complement your natural thinking style rather than oppose it.

Breaking Out of Linear Thinking

People give me a funny look when I tell them I do my best work standing in line at 7-Eleven. “How can you be working if you’re at the store?” Mundane activities like washing dishes, folding clothes, and showering have an emptying effect. This declutters your thoughts and gives you the cognitive space to organize information, reframe problems, and imagine new solutions.

Have you heard of Archimedes’ bath-time discovery? Hieron, the king of Syracuse, tasked Archimedes with determining whether his crown was made of pure gold. Archimedes thought long and hard but couldn’t come up with an answer.

While filling a bathtub, he noticed that the water spilling over the edge as he got in was equal to the weight of his body. Because Archimedes knew gold was heavier than the potential substitute metals, Archimedes had his answer. Without realizing he was naked, he ran down the streets shouting, “Eureka!” This “Eureka moment” demonstrates how insights happen when our minds disconnect from direct problem-solving.

When you’re stuck working on a problem, switching gears is often the best way to break out of the traditional thought cycle. This mental decluttering during routine tasks explains why many breakthroughs happen when we’re not actively focused on a problem.

The human mind is a natural pattern-making system. It collects information from our environment and organizes it into recognizable patterns. Once these patterns form, the mental selection mechanism takes over, filtering information to keep what’s necessary for the task at hand. It can only select patterns, not make or analyze them. While this can be effective for many problems, it can prevent us from seeing connections that lead to breakthrough insights. Vertical thinking is selective thinking.

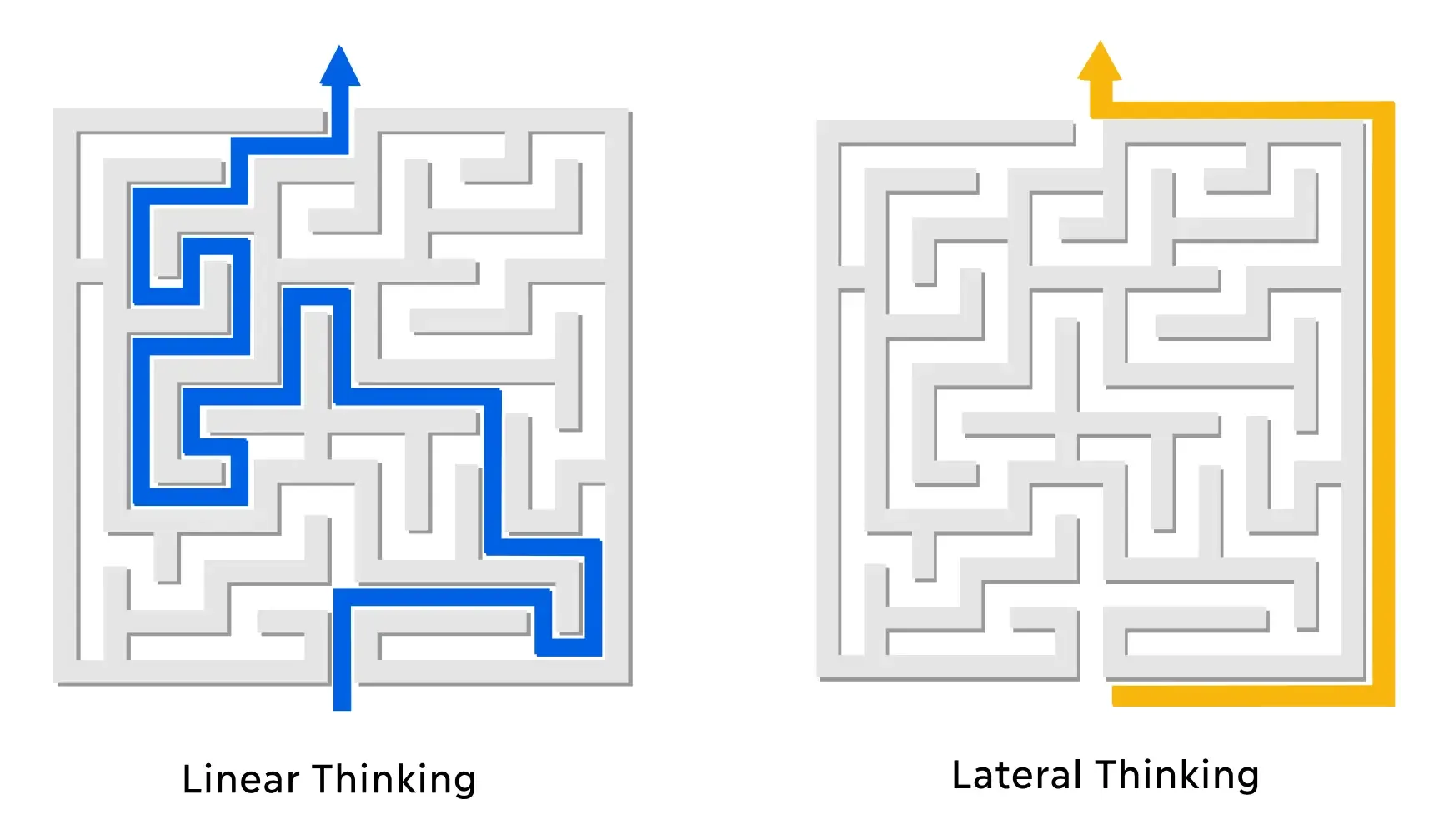

Vertical thinking follows a predetermined path, while lateral thinking breaks patterns by approaching problems from different angles.

Vertical thinking follows a predetermined path, while lateral thinking breaks patterns by approaching problems from different angles.

Linear Thinking Is Selective

When you’re in vertical thinking mode, you take a position and build on it to progress your thinking on possible solutions. This is the type of thinking we’re taught in school, i.e., logic, which determines our thought movement along a sequence of events. Past information provides a reference for our current position and potential next steps.

For example, in chess, each piece has a predetermined pattern of movement based on the rules. The longer you play, the more experience you gain. This creates a foundation for your strategy. While this approach is powerful in familiar situations, it limits pattern recognition when faced with new challenges.

Lateral Thinking Is An Insight Tool

The need for lateral thinking comes from the limitations imposed by our pattern-selecting mind. We become trapped in old patterns when we focus our problem-solving methods solely on linear thinking. Lateral thinking compensates for these disadvantages by deliberately breaking established patterns to create new connections.

Lateral thinking is a systematic approach to using information to restructure creativity and insight. Edward DeBono coined the term to explain the form of thinking that is not linear, sequential, or logical. Merriam-Webster defines lateral thinking as “a method for solving problems by making unusual or unexpected connections between ideas.” According to DeBono, the simplest explanation of lateral thinking comes from the statement, “You cannot dig a hole in a different place by digging the same hole deeper.”

Lateral thinking deals with perceptions, concepts, and starting points. Instead of trying to figure out what’s true, lateral thinking explores “possibilities” or “what might be.” Linear thinking alone often leads to a lack of insights. Lateral thinking emphasizes different perceptions, lenses, and ways of seeing things that logic can’t replicate.

“You cannot dig a hole in a different place by digging the same hole deeper.” —Edward De Bono

The Challenge: Architecting A Blockchain Solution Under Pressure

One practical example of lateral thinking involves simply taking a break when getting stuck on a problem while working on a very tight deadline. One project I worked on involved architecting a blockchain infrastructure solution for a multi-national corporation with subsidiaries involving automobile manufacturing and financial services. The company wanted to understand how blockchain technology, specifically stablecoins, might reduce banking transaction fees throughout the supply chain.

The information provided was vague to say the least, and with no guardrails in place in terms of requirements, I felt the pressure to perform. I understood that the client had one of the most stringent process infrastructures worldwide, and without understanding the systems and controls, the best I could do was guess. With less than 24 hours to create a high-level architecture, the best I could do was detail my understanding of the process deficiencies and their desired outcomes to give the project structure.

Was I the right person to design such an architecture for an invisible problem? Did I even know enough about the situation to decide what was worth prioritizing? How could I create anything worth evaluating in such a short time window?

Thankfully, I recently read the book Lateral Thinking by Edward De Bono. The concepts discussed in the book helped me get outside of traditional linear thinking mode and imagine future possibilities rather than absolute certainties. One thing that jumped out at me in the book was De Bono’s definition of a problem. A problem is simply the difference between what one has and what one wants.

The client had a large, sustainable business supporting thousands of suppliers. When the company received parts from these suppliers, it had to pay an invoice, and the invoice payment process naturally involved banking fees. Things like quality defects, partial deliveries, etc, affected the accounts payable ledger, which frequently complicated and increased the transaction fees.

In the book, De Bono mentions that there are three types of problems:

- The first type requires more information or better techniques for handling information and determining a solution.

- The second type requires no new information, but rearranging the information already available: an insight restructuring.

- The third type of problem is the problem of no problem. The adequacy of the present arrangement blocks the situation from moving to a better solution. There’s no point in focusing efforts to reach a better solution because those involved aren’t even aware that there is a better one. Not realizing there is a problem, and that things can be improved.

Fully resolving the client’s situation required additional information; however, resolving my problem, i.e., turning in a draft, required rearranging the information I already had. While the client was facing the first problem type, I needed to realize that I could use problem type II as a starting point.

Using Six Thinking Hats to Structure Creative Thinking

Before moving forward, I needed a game plan to reduce my workload and stress levels. Without a game plan, I easily get lost in the details of the situation, which wastes time and energy. This led me to apply the Six Thinking Hats.

The Six Thinking Hats is a structured thinking tool that organizes our thoughts like an orchestra. Each hat provides focus, allowing us to progress along a chosen path until we have completed each one. At the end, a fully formed and organized picture emerges.

- White Hat: Focus on facts, information, and data

- Red Hat: Express emotions, feelings, and intuitions

- Black Hat: Apply critical judgment and caution

- Yellow Hat: Think positively about benefits and opportunities

- Green Hat: Generate creative ideas and possibilities

- Blue Hat: Manage the thinking process itself

First, I needed to put on the white hat, so I reviewed the spreadsheet to better understand the project and orient my thinking. Just as I started to grasp the complexity of the situation, I began to feel the pangs of anxiety setting in. Negative thoughts started flooding my head.

“We’re going about this backward by trying to force a solution onto a problem. We should start by fully understanding the issues before we try to come up with solutions.”

Confusion is the enemy of good thinking. — Edward De Bono

After a few moments, I realized what was happening. At some point in the process, I had slipped into Black Hat thinking mode. We enter a mode of judgment and negativity when we wear the black hat. Many people misrepresent the Black hat as the bad hat, which isn’t the case at all. Black Hat thinking is excellent when used at the right time. However, starting a project of this magnitude wasn’t the right time for me to use this mode.

From Concept to Solution: The Creative Process in Action

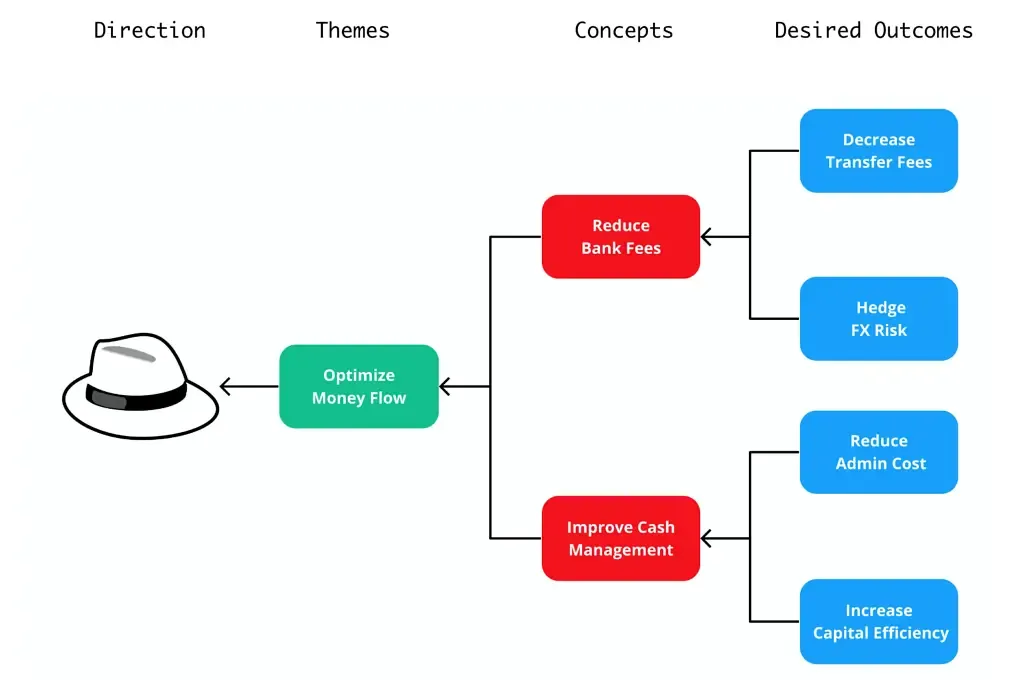

Because I work best through activities, I created a mind map representing the six hats. This mind map created a blueprint for moving along each domain of the creative process (the blue hat). The Excel spreadsheet formed the structure for housing information related to the project (the white hat). I broke each row and column into central themes, concepts, and desired outcomes, including reducing bank fees and improving cash management. This structure allowed me to structure ideas to ensure they fit into the theme.

“White Hat Thinking” organizes information into clear concepts and desired outcomes.

“White Hat Thinking” organizes information into clear concepts and desired outcomes.

Let’s assume the client wanted to decrease banking transfer fees, hedge foreign exchange risk, reduce administrative costs, and increase capital efficiencies. Working backward, we can organize these goals into core concepts, including reducing bank fees and improving cash management. These concepts form the central theme of “Optimize Money Flow.”

After reframing the spreadsheet information, I went through the other three modes, including green, red, and yellow hat thinking. By the end of the process, more than fifteen ideas were developed for reducing costs and increasing revenue under the following insight themes including:

- Stablecoin Opportunities

- Workshop Opportunities

- Smart Contract Opportunities

- Security Token Opportunities

- Software As A Service (SAAS) Opportunities

Next, I created a business process flow diagram. By diagramming my assumptions of their business processes at a high level, I considered how they might implement my ideas. Once the flow diagram draft was completed, I attempted to integrate each solution into the future state.

The Creative Block: When Linear Approaches Fail

Integrating all these solutions wasn’t as straightforward as I’d hoped. I felt like I was flying blind, making assumptions about processes and structures I didn’t understand. How was I supposed to diagram each process confidently without all the information?

Before long, the sun began peaking through my curtains. I’d worked all night. I needed to turn in my draft by the afternoon, so I called a colleague to help me think through and reframe the ideas. After a while, I realized several of my core themes didn’t make sense to her, and if she didn’t understand them, the client certainly wouldn’t. I needed to take a break, but there wasn’t any time. Frustrated by my lack of insights and tired from the all-nighter, I needed some coffee to refuel.

The 7-Eleven Breakthrough: Why Environment Changes Spark Insights

I live in Japan, where 7-Elevens are on every corner. The information swirled around in my head as I walked down the street. What would the process look like if it were easy? Upon entering the sliding storefront doors, the aroma of fresh coffee greeted my nostrils, a slowed-down acoustic version of “Daydream Believer” filled my ears, and bright lights pierced my eyelids.

I walked around the maze of snacks leading to the cashier. Just as I entered the queue, I noticed my favorite old-fashioned donut with chocolate frosting on the shelf. Should I risk losing my position? It was the last one, after all, so I jumped out of line and got right back in. I paid for the coffee and donut, and walked over to the coffee machine to place my cup on the device. Upon pressing the button to start the process, an invisible sensor determined the size and blend of the coffee I’d purchased. As the beans began to grind, a rush of insights flooded my head.

Pattern Recognition Across Domains

The coffee machine’s placement near the entry and exit wasn’t random—this setup was consistent across every 7-Eleven I’d visited in Japan.

Clearly, 7-Eleven had studied customer behavior to determine the optimal location for greeting people with the sight and smell of fresh coffee. The strategic donut placement along the checkout aisle triggered impulse purchases while customers waited in line. People would pay, move to the exit, and place their cup under the machine with visible anticipation on their faces, which in turn encouraged others to buy coffee too.

I was observing a perfectly orchestrated system that had just transformed my simple ¥150 coffee purchase into a ¥247 transaction that included a donut I hadn’t planned to buy. 7-Eleven had created a self-organizing system that optimized complementary product sales with minimal friction.

That was it! We needed to propose a self-organizing system to optimize the client’s process!

I rushed home, explained the insight to my colleague, and frantically began diagramming the solution. The retail store pattern had provided the exact template we needed for optimizing value flow in a corporate supply chain. Within forty-five minutes, we had transformed this convenience store insight into a comprehensive blockchain architecture, diagrammed, written up, and ready for translation into Japanese.

The Solution: A Self-Organizing Blockchain Based System

Rather than thinking of each specific problem, we needed to think of the whole ecosystem. The solution would require implementing a self-organizing system consisting of two main components:

- Smart contracts to record the receipt and movement of materials

- A bond-backed stablecoin to facilitate the transfer of value for the movement of goods

I specifically architected the stablecoin to be backed by corporate bonds the company already regularly issued. This served two important purposes: reducing reliance on traditional reserve assets and creating a natural integration point with their existing financial processes.

Whenever the system receives goods, they are recorded in the smart contract, automatically issuing stablecoins equivalent to the value received. This combination reduced administrative work and banking fees while creating a seamless value transfer mechanism throughout their network.

How Lateral Thinking Made the Difference

Here’s how lateral thinking helped me re-imagine the system so quickly. Had I continued working without pausing, I might have spent hours diagraming without noticeable progress.

The Six Thinking Hats provide structure

Analyzing the spreadsheet using the six thinking hats framework allowed me to consider multiple perspectives. I wrote down all the facts, negative thoughts, emotions, opportunities, and ideas. By focusing on each aspect individually, I avoided the confusion created by trying to process too much simultaneously. With each focus area laid out next to each other, the big picture presented itself for discovery.

Diagramming Exposed Gaps in Thinking

When I tried to diagram the solution, I realized there were holes in my thinking. Although I had all the relevant information on paper, I hadn’t yet thought it through. Insights take time to develop because we often need to reframe the situation. The creative process requires flexibility in our thinking. We have to be aware of the need to switch between vertical and lateral thinking modes. Rather than keep digging the same hole deeper, I needed to start from a different angle.

The Creative Pause: Why the 7-Eleven Trip Changed My Thoughts

Going to 7-Eleven removed me from the thinking mode needed for diagraming. Exposure to the new environment provided an opportunity to reflect and assess the situation from a different perspective. The creative pause is one of the simplest yet underrated productivity hacks available.

The deliberate process of interrupting the current flow of thoughts requires discipline and practice. Anyone who wants to be more creative should implement the creative pause into their routine. Investing in this simple habit increases the ability to be more innovative. Yet many people refuse to take even a few minutes to let their minds wander.

Implementing This Approach in Your Work

The 7-Eleven Effect isn’t just dumb luck. You can repeat this insight-generating process by combining structured thinking with strategic breaks. Next time you’re stuck, try these steps:

-

Prepare the foundation:

- Write down the problem

- Collect relevant information

- Reframe your understanding

-

Implement a creative pause:

- Walk away from the problem

- Change your environment completely

- Do something mindless

- Try to limit the break to 1-hour

-

Capture insights immediately:

- Bring a notepad with you

- Write down ideas as they come

- Look for patterns or connections

- Sketch your ideas if it helps

-

Apply insights to your original problem:

- Connect the dots between patterns and the problem

- Look for system-level solutions instead of symptom fixes

- Test your solution against the requirements

- Try reimagining entire solution, not just tweaking what you have

Cognitive Profile Connection

Understanding how your brain works can dramatically increase your creativity. The approach I’ve outlined works well for people with problem-solving styles similar to mine. According to the Basadur Problem Solving Profile, I’m a “Generator.” Generators excel at identifying opportunities and starting new projects. If you enjoy brainstorming, spotting connections between unrelated ideas, or constantly generating new approaches, you might share these tendencies.

The Six Thinking Hats approach organized my scattered thinking, while the creative pause technique gave space to explore and iterate on my ideas.

You can adjust this approach to match your natural thinking style, even if your thinking style differs. Perhaps you’re more analytical or implementation-focused. The key is recognizing when you’re stuck and deliberately creating space for a new perspective.

You might be surprised by the creative ideas that emerge when you step away from your work, change your environment, and let your mind make new connections.