Perception Gaps: The Expensive Truth About High-Trust Teams

Key Takeaways

- The Hidden Danger: Teams with similar cognitive profiles (cognitive harmony) create more dangerous perception gaps than diverse teams because shared blind spots go unexamined

- The $180 Billion Cost: 53-74% of AI implementations fail, with perception gaps being one of the most insidious causes, hidden until catastrophic misalignment is revealed

- The Challenge: High-trust cultures and constant communication (like busy Slack channels) can mask fundamental misunderstandings about project goals and requirements

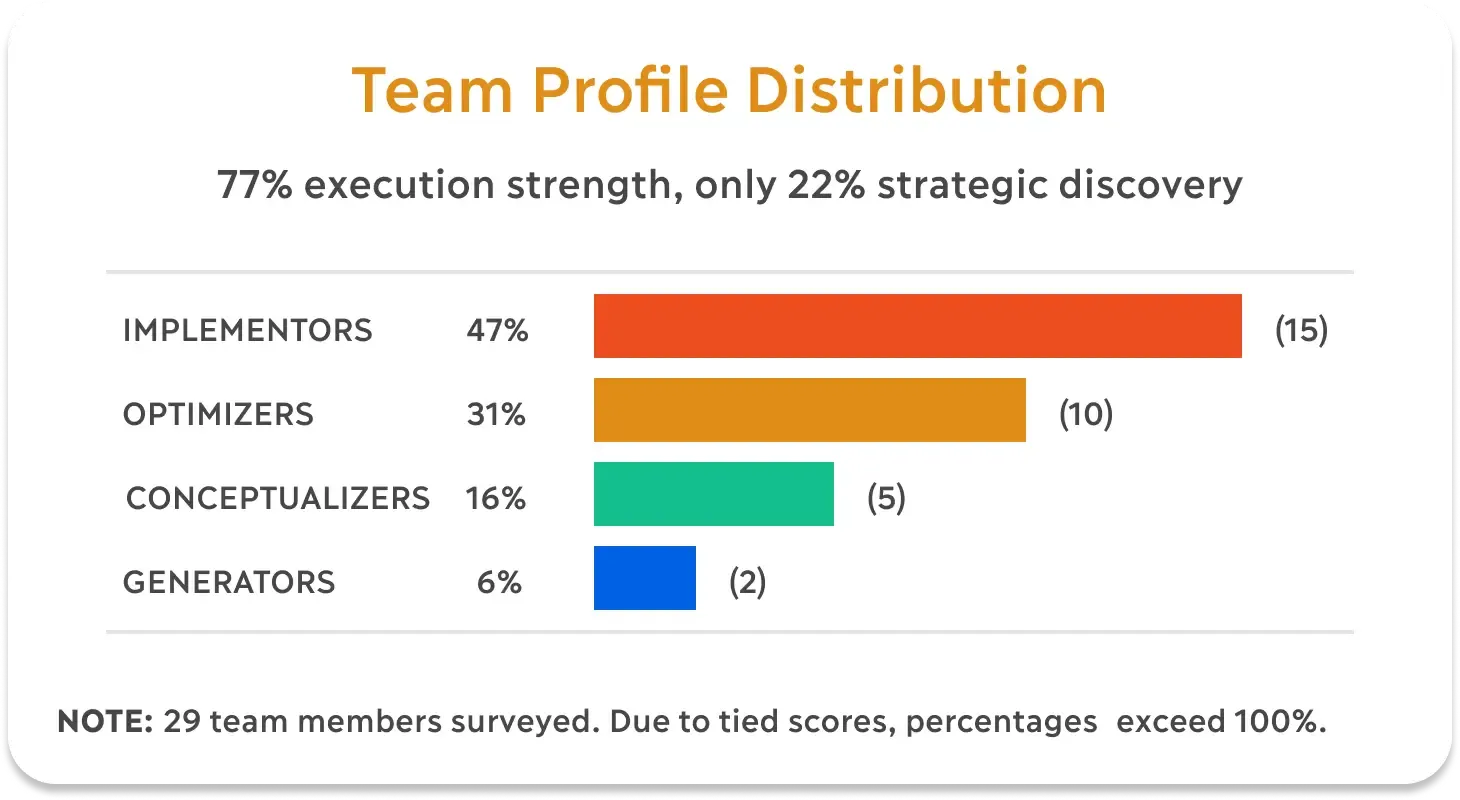

- The Evidence: In a 29-person team, 77.3% were Optimizers/Implementers focused on execution, while only 2 Generators (6.2%) were present to ask “what else might this be?”

- The Solution: Socratic inquiry creates safe conditions for teams to discover their misalignments through visual exercises and systematic questioning

With AI investments projected to reach $243 billion in 2025 and failure rates as high as 74%, organizations risk wasting up to $180 billion. Don’t believe me?

Picture this scenario. Last year, your company earmarked funds to upgrade legacy systems with AI features. You made a strategic bet that AI would provide the boost your products need to remain competitive.

Your name and credibility depend on the success of this project. Sparing no expense, you approved and hired the best and brightest people to do the work.

The project team spent months planning the technical integration with the cloud service provider (CSP) to address “critical business” risks. You had weekly meetings to discuss the overall progress, risks, and opportunities. At every step, the implementation manager assured you that the project was on track.

Then it happens…

A casual conversation in the cafeteria with a senior engineer turns into an Information tornado of confusion. He tells you all about the features and issues he’s slogging through. What he describes is far from what the leadership team imagined.

You probe for information, hoping he’s delusional. Then, a few key team members join in the discussion. Before long, you start to realize that your dream project just morphed into a business nightmare.

You schedule an emergency meeting with everyone to get the facts right. Before long, reality smacks you upside the head, the team is building the wrong solution. One that’s fundamentally different than what your strategy is aligned around.

Yes, you can still turn the ship around, but marketing materials have already been released that describe product features that don’t exist. Your regulatory compliance obligations rely on requirements that haven’t been started. To top it all off, you’re supposed to demo the product to your key investors who are depending on the project to succeed.

This scenario isn’t the result of a simple miscommunication. Scenarios like this occur because of perception gaps—everyday situations where team members think they’re aligned while simultaneously holding completely different mental models of success. When left undiscovered, such gaps grow wider and more complex. Before long, you find yourself with a “wicked problem” that’s nearly impossible to manage.

In the era of AI systems integration, wicked problems like this (Holtel, 2016; Rittel & Webber, 1973) will become increasingly pervasive and costly. Teams that aren’t aligned on what they’re building and why they’re building it will derail even the most promising initiatives. The lack of understanding around AI solutions makes project teams even more susceptible to this phenomenon (McMillan & Overall, 2016).

With AI investments projected to reach $243 billion in 2025 and failure rates as high as 74%, organizations risk wasting up to $180 billion. What’s particularly alarming is that AI projects fail at twice the rate of non-AI IT projects (Ryseff et al., 2024), suggesting that the complexity of AI amplifies existing organizational dysfunction.

The $180 Billion Problem Almost No One Recognizes

The global AI market is projected to reach $243 billion by 2025 (Statista, 2025). Recent reports from Rand estimate that between 53% and 74% of implementations fail to deliver the expected value (Ryseff et al., 2024). With 74% of implementations potentially failing, this represents up to $180 billion in wasted AI investments annually.

Even more disturbing is that nearly half of technology leaders (49%) acknowledge that AI is “fully integrated” into their core business strategy (PricewaterhouseCoopers, n.d.-a), yet haven’t even completed a preliminary implementation risk assessment (PricewaterhouseCoopers, n.d.-b).

*Not knowing something’s broken is an expensive problem—a case study in cognitive complexity.

A few years ago, I was tasked with designing finance controls for a centralized crypto-exchange (CEX) seeking a license to operate as a regulated exchange under the Malta Virtual Financial Assets (VFA) framework. The team worked diligently for about six months before my joining to develop the backend operating systems and front-end user interfaces.

The team took pride in its identity as an agile crypto startup. Communication channels were buzzing with activity. Slack painted a picture of seamless collaboration. Notifications pinged with quick status updates, emoji reactions, and articles on crypto industry trends validating the progress.

On the surface, the project seemed to be running well. The team had progressed beyond the minimum viable product (MVP) and was working feverishly to progress toward launching the exchange. Everyone seemed excited about the direction.

Typical challenges appeared when looking below the surface.

Depending on a project’s complexity, I may spend a few days or weeks reviewing documentation. What core assumptions do the business model, systems architecture, and compliance requirements rely upon? In this case, there were no artifacts describing any of the assumptions: no project charter, no requirements documentation, no budget. The project evolved from an idea to a nearly 30-person team with free rein to figure things out as they went along.

When I asked the compliance officer for the compliance matrix, I received a don’t look over here type of reply. “*What’s a compliance matrix? I’ve only been here for two months. Somebody else is supposed to provide that…”

When I asked the product manager for the user journey map, system diagrams, and product user stories, I was told the team was too busy building to create those.”*This isn’t like Aerospace, Roy. We’re a crypto startup. We do things agile.” In the team’s mind, agile meant no documentation. This was troubling, given that the entire strategy relied upon obtaining a license that required extensive documentation.

I asked the CFO how he handled problems like this within the company. His response, “I hired a guy named Roy, and all my problems magically went away.” Oh boy! The situation looked bleaker with each passing day.

How was I supposed to design the budget, financial processes, and controls around an architecture that not only didn’t exist, but hadn’t been planned?

The Vulnerability of Shared Misunderstanding

When I arrived in Singapore to align with the implementation team, what I discovered was eye-opening, to say the least. I sat in the room with the dev team so I could observe the dynamics. By coincidence, a series of Slack messages began to appear, sparking an entire conversation.

Multiple messages began flying around. What was odd about this situation was that the team members were sitting right next to each other. Rather than have a meaningful conversation, they fired off half-complete messages. Slack would inform that someone was typing, and everyone started typing their responses.

When I witnessed a standup meeting, it seemed more like a routine role call than a meaningful discussion about progress challenges. Team members nodded in agreement so they could get back to building.

I presented my findings to David, the product owner.

He grew visibly frustrated that I didn’t understand the team culture. He wanted me to attend a one-on-one with Michael, the project manager. This would prove that everyone was indeed on the same page, and I didn’t get what they were doing.

During the meeting, David threw out a barrage of complex requirements. He’d prepared a document outlining what he’d observed in the crypto market, and wanted to evolve these features. Trade mining was now the rage, and the team needed to jump on this new trend.

Michal nodded in agreement. “Yep, no problem, we can totally do that.” David seemed satisfied that everyone was on the same page and wanted to adjourn the meeting so he could get back to work.

But I knew better. “Hey, Michael, I’m not sure I fully understand the situation here. Could you help me understand? Would you mind drawing a diagram of what David requested you to communicate to the team? Also, could you include how this integrates into the existing architecture?”

“Sure, no problem. Here’s what we’re building.” Michael started drawing on the whiteboard.

Within a few moments, David grew agitated. “What are you drawing, Michael? That’s not how the system works.”

“I’m drawing what you asked for,” Michael replied.

David’s voice grew terse. “That’s not it at all, and what’s all this stuff over here. Where are the features that drive the token creation, distribution, and ownership reports? We’ve been talking about these requirements for almost two months now. How do you not know what the team is building?”

“This is what we’re building…” Michael looked confused.

The tension between the two began to rise.

In that moment, both David and Michael began to realize they were operating with completely different mental models. Each held different views of the system components, priorities, and success criteria.

This wasn’t a simple miscommunication. It was a perfect example of a perception gap. Each held different understandings, but couldn’t see them because they hadn’t invested sufficient time and energy in the dialogue required to fully understand them.

In the case of data-intensive applications such as the one they were building, simply writing down a list of features isn’t enough. You have to visualize each system component to show the relationship connections that drive requirements.

This pattern mirrors what researchers at RAND Corporation have documented in failed AI projects: “In failed projects, either the business leadership does not make themselves available to discuss whether the choices made by the technical team align with their intent, or they do not realize that the metrics measuring the success of the AI model do not truly represent the metrics of success for its intended purpose (Ryseff et al., 2024).”

What makes these situations particularly challenging is that no one realizes the problem until a specific chain of events makes the problem obvious. This can be done proactively through dialogue or reactively when symptoms begin to emerge. This insight connects directly to what Edward De Bono identifies as a “Type III problem” or “the problem of no problem” (De Bono, 2016, pp. 53-55).

When we don’t realize a problem exists, we make no effort to address it. The team had been moving forward with implementation, appearing to make progress, while heading toward an inevitable clash of unmet expectations.

Perception gaps are more complex than simple miscommunication.

In any project, team members are constantly trying to prove they belong in the group. The group must have deep trust among its members before someone feels comfortable admitting their vulnerabilities.

New team members are expected to ask questions. Those involved since the beginning are often less likely to admit they don’t understand key objectives. Cultural dynamics can make this even more difficult to admit.

In this case, the team had a high level of trust, as they worked unchallenged on the tasks they deemed important. However, this was a blind trust as no one recognized the problem. This high-trust culture paradoxically prevented the asking of questions that build genuine trust.

Everyone operated within their zone of responsibility rather than admitting confusion or seeking clarification. In complex and ambiguous environments, teams often resort to comfortable routines and assumptions to cope. Such mechanisms usually prevent the discovery of critical misalignments.

To better understand the underlying team dynamics.

I administered the Basadur Creative Problem Solving Profile (CPSP). This validated assessment measures cognitive preferences across four stages of the creative problem-solving process: Generating, Conceptualizing, Optimizing, and Implementing. Looking at the team’s profile distribution revealed an imbalance that directly contributed to the symptoms I was observing:

The data showed the team was heavily skewed.

- Implementers dominated at 46.9% - These team members excel at getting things done but may not question whether they’re doing the right things.

- Optimizers were strongly represented at 31.2% - These team members focus on analyzing and refining solutions, assuming the problem is well-defined.

- Conceptualizers were underrepresented at 15.6% - These team members specialize in clearly defining problems and seeing the big picture.

- Generators were nearly absent at only 6.2% - These team members excel at identifying opportunities and seeing things from different perspectives.

The underrepresentation of generators and conceptualizers meant people were less likely to ask probing questions, define the big picture, and seek alternative solutions that focus on the big picture. This meant that 77% of the team were focused on refining the existing direction and implementing it, even if they were going down the wrong path.

The distribution explained the dynamic I had observed; the team had created a cognitive echo chamber where assumptions went unchallenged. David, an Optimizer, naturally excelled at analyzing and fine-tuning solutions. Michael, an Implementer, wanted to make progress on what the team already understood. Neither were naturally inclined to seek out alternatives, define the problem, and ensure shared understanding before moving to implementation.

AI projects are not immune to the effects of perception gaps.

Recent research indicates that between 53% and 74% of AI implementations fail to deliver the expected value (Ryseff et al., 2024).

While many factors contribute to these failures, perception gaps rank among the most insidious because they remain hidden until it’s too late. As the RAND study found, “Misunderstandings and miscommunications about the intent and purpose of the project cause more AI projects to fail than any other factor” (Ryseff et al., 2024).

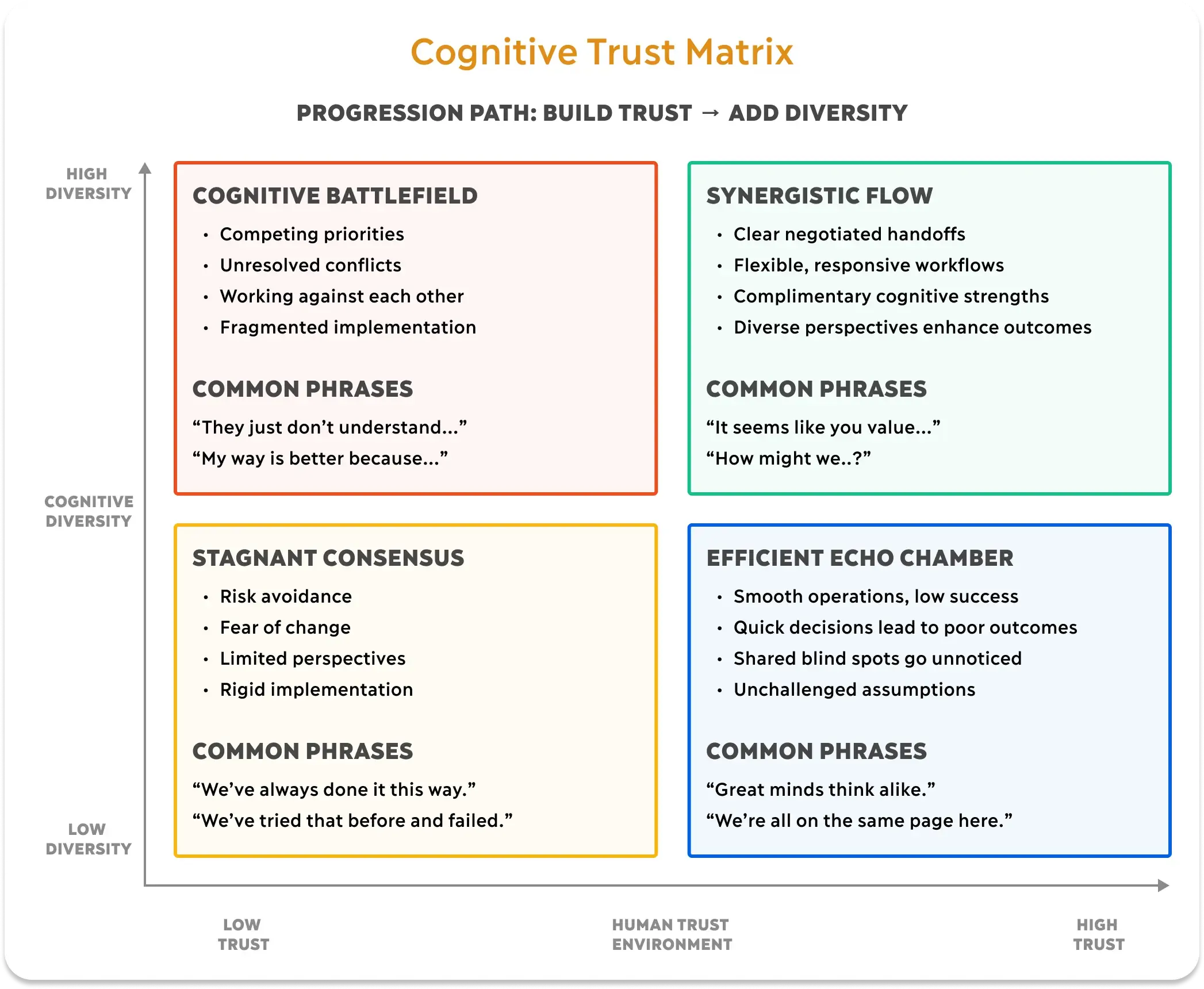

I created the Cognitive Trust Matrix based on my experiences working with teams, as seen in the case study above. The matrix consists of two dimensions.

-

Cognitive Diversity: How many different thinking styles are present (Generators who discover, Conceptualizers who define, Optimizers who refine, Implementers who execute);

-

Trust Environment: Whether people feel safe to question and challenge the consensus mechanisms surrounding strategic objectives.

The Cognitive Trust Matrix reveals four patterns that teams fall into:

- Cognitive Battlefield: Diverse thinking but low trust = competing perspectives and fragmentation

- Stagnant Consensus: Similar thinking and low trust = fear-driven paralysis

- Efficient Echo Chamber: Similar thinking but high trust = smooth operations in the wrong direction (our trap)

- Synergistic Flow: Diverse thinking and high trust = the target state where differences enhance outcomes

The team’s over-reliance on optimization and implementation pushed them into the “Efficient Echo Chamber” quadrant. High trust and smooth operations masked the fact that they were efficiently building the wrong product. The common phrase “We’re all on the same page here” is a typical warning sign.

According to RAND, 84% of experienced AI practitioners interviewed cited leadership-driven failures as the primary reason AI projects fail (Ryseff et al., 2024). This insight closely aligns with the pattern of the perception gap. Business leaders, technical teams, and operations staff hold fundamentally different mental models of what an AI implementation should achieve, making failure almost inevitable.

The team in question spent months developing a solution that didn’t match the product owner’s vision. Because the team shared similar thinking styles, no one questioned whether they shared the same mental model. This drained the company of valuable resources that could have been better utilized.

In AI implementations, these dynamics become even more dangerous. AI systems rollouts are still in the infancy stages. Very few have a solid understanding of use cases, limitations, and best practices. When everyone assumes the AI will work a certain way, no one asks the uncomfortable questions that drag the truth into the light of day.

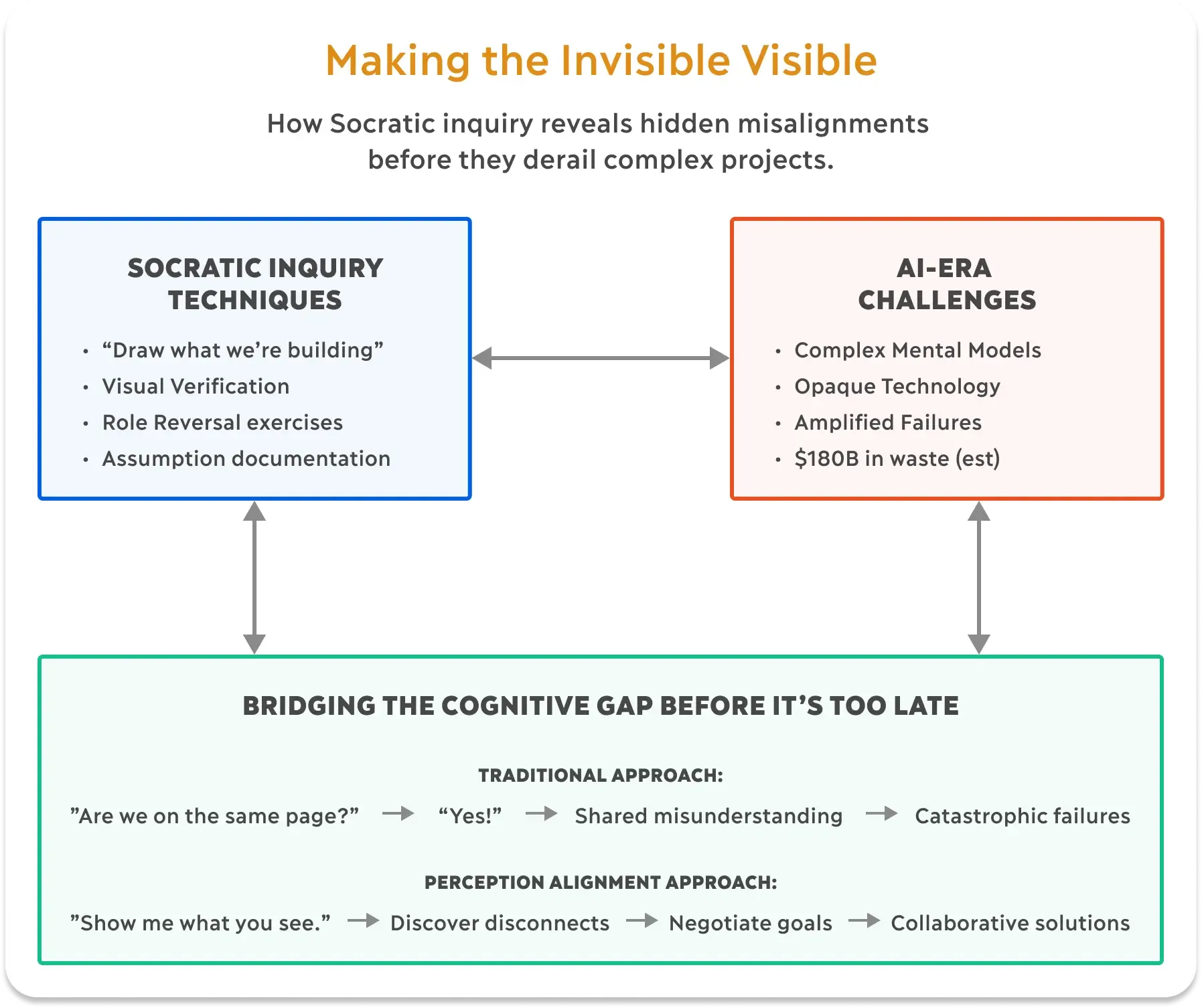

Socratic Inquiry: Making the Invisible Visible

Directly pointing out the problem would have created defensiveness and damaged my relationship with the team. Instead, I employed Socratic inquiry. This created a condition where David and Michael could discover the misalignment themselves.

This approach builds upon the classical Socratic methodology, which involves the systematic use of questions to expose hidden assumptions and contradictions.

When I asked Michael to draw what he understood, I was applying core Socratic technique: establishing common ground, then systematically revealing assumptions through guided discovery. This 2,500-year-old method provides a foundation for organizational alignment.

What Michael drew wasn’t just a diagram; it was a manifestation of his mental ‘Form’ of the system, in the Platonic sense of an ideal representation. David’s immediate reaction revealed that they had been operating with completely different Forms while believing they shared the same conceptual reality.

The solution isn’t more meetings or better documentation. It’s creating conditions where people can safely identify and address their misaligned assumptions.

This approach offers several advantages:

- It builds psychological safety by allowing self-discovery rather than external criticism

- It creates shared visual reference points that make abstract mental models concrete

- It avoids defensive reactions that direct confrontation triggers

- It facilitates immediate collaborative problem-solving rather than blame assignment

- It systematically exposes foundational assumptions that create perception gaps

- It respects cultural norms while challenging hidden assumptions

When team members discover divergent mental models themselves through Socratic inquiry, they take ownership of the alignment solution rather than feeling criticized or intellectually inadequate.

Verification Techniques for AI Implementation

For AI implementation specifically, I recommend these additional verification techniques:

- AI-Human Workflow Mapping: Create visual maps of where AI and humans interact, with explicit definition of expectations at each transition point.

- Trust Calibration Exercises: Develop structured activities that help users understand both the capabilities and limitations of AI systems.

- Value Translation Sessions: Create forums where technical teams must explain AI features in terms of business/user value, and vice versa.

The Socratic inquiry approach works because it recognizes and adapts to different thinking styles, creating conditions for genuine discovery. This method directly addresses the unique challenges of AI implementation projects. Complex and ambiguous technical projects of this nature are likely to amplify perception gaps.

By making divergent mental models visible and creating shared reference points, teams can identify and bridge these gaps before they lead to costly failures. Rather than forcing consensus, it allows team members to maintain their cognitive preferences while building shared understanding.

Conclusion

Perception gaps represent one of the most challenging aspects of team collaboration because they exist in our blind spots. We often don’t realize what we don’t know, and we don’t recognize that others are operating with different mental models until it’s too late.

The financial impact is staggering. With 53-74% of AI implementations failing to deliver expected value (Ryseff et al., 2024), perception gaps represent a critical business vulnerability that few organizations consciously address.

The key insight you should take away is this: sufficient dialogue to discover shared understanding doesn’t happen automatically, especially in environments where people feel intellectually vulnerable. It requires deliberate effort, psychological safety, and systematic inquiry into foundational assumptions.

Counterintuitively, cognitive harmony, not diversity, often creates the most dangerous perception gaps. When team members share similar cognitive profiles, they develop shared blind spots, allowing divergent mental models to flourish undetected. By understanding how different cognitive profiles shape perception, we can implement Socratic inquiry techniques to make invisible gaps visible before they derail our projects.

Remember that confusion is the biggest enemy of good thinking (De Bono, 2016). When we recognize that perception gaps emerge from cognitive alignment patterns rather than individual competence, we can address them systematically and build stronger, more aligned teams.

Note: Names, locations, and identifying details in this article have been changed to protect client confidentiality. The events described are real, but specific references have been modified to maintain privacy while preserving the essential lessons learned.

References

Basadur, M., Gelade, G., & Basadur, T. (2014). Creative Problem-Solving Process Styles, Cognitive Work Demands, and Organizational Adaptability. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 50(1), 80–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886313508433

De Bono, E. (2016). Lateral thinking: A textbook of creativity (pp. 53-55). Penguin Life.

Goldstone, R. L., & Barsalou, L. W. (1998). Reuniting perception and conception. Cognition, 65(2), 231–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-0277(97)00047-4

Holtel, S. (2016). Artificial Intelligence Creates a Wicked Problem for the Enterprise. Procedia Computer Science, 99, 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2016.09.109

McMillan, C., & Overall, J. (2016). Wicked problems: Turning strategic management upside down. Journal of Business Strategy, 37(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBS-11-2014-0129

PricewaterhouseCoopers. (n.d.-a). 2025 AI Business Predictions. PwC. Retrieved June 10, 2025, from https://www.pwc.com/us/en/tech-effect/ai-analytics/ai-predictions.html

PricewaterhouseCoopers. (n.d.-b). PwC’s 2024 US Responsible AI Survey. PwC. Retrieved June 10, 2025, from https://www.pwc.com/us/en/tech-effect/ai-analytics/responsible-ai-survey.html

Rittel, H. W. J., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155–169. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4531523

Ryseff, J., De Bruhl, B. F., & Newberry, S. J. (2024). The Root Causes of Failure for Artificial Intelligence Projects and How They Can Succeed: Avoiding the Anti-Patterns of AI. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2680-1.html

Singla, A., Sukharevsky, A., Yee, L., Chui, M., & Hall, B. (2025). The State of AI: How organizations are rewiring to capture value. Quantum Black AI by McKinsey. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/quantumblack/our-insights/the-state-of-ai

Statista. (2025). Artificial Intelligence - Global Market Forecast. Retrieved May 7, 2025, from https://www.statista.com/outlook/tmo/artificial-intelligence/worldwide