Reading the Room: What My Daughter's Second-Grade Art Class Taught Me About Organizational Dynamics

Key Takeaways

- Environmental design drives behavior: What appears as individual performance issues often reflects a mismatch between cognitive style and environmental demands, which can be addressed through systematic observation and targeted intervention.

- Cognitive styles predict failure patterns: When structure-oriented talent is forced into ambiguity-driven roles, breakdown is predictable and preventable through proper assessment and evaluation.

- Small process changes transform outcomes: When environmental constraints are fixed, procedural modifications can bridge the gap between cognitive requirements and organizational needs.

“So you want me to tell the teacher that the room is making Waka act up in class?” Waka’s mom wasn’t happy with my assessment and wasn’t looking forward to translating it into Japanese.

“Well, the room is a big part of the problem,” I replied.

“That’s the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever heard,” she folded her arms and shook her head. She wasn’t wrong. Even saying it out loud, I felt it sounded improbable.

We were experiencing every parent’s nightmare; our eight-year-old daughter was bullying children in art class.

The situation worsened over the last few months, until things reached a boiling point. Waka got upset in class over a silly comment a boy made about her project, and she kicked him. When the teacher confronted her, she screamed and ran away from school. She made quite a spectacle, according to her homeroom teacher’s retelling of the story—several teachers chased her down, tackled her, and brought her back safely.

The teachers were dumbfounded. This was the first time they’d dealt with a second-grade girl behaving in such a way. As the only half-Japanese student, writing Waka’s troubles off to cultural dynamics would have been easy. But that wasn’t what was happening here.

That morning, I put on my flashy grey mohair suit and a bright, geometric-patterned tie. Waka didn’t like the spotlight. Knowing I would be in the classroom was bad enough, but the thought of me showing up beaming for everyone to see was downright unimaginable.

“No, no, wear something normal,” she pleaded.

We showed up about fifteen minutes after class started. Waka’s homeroom teacher ushered us into the room, and we stood in the back. I was a bit nervous about the whole thing. Maybe this outfit was a little much for a group of second graders.

Her mother and the homeroom teacher spoke in Japanese, expressing concern over the situation. They translated important details so that I understood.

We were told that Waka would often become frustrated in class, yell, and disrupt the attention of the other students.

The homeroom teacher explained that students draw a lottery number each day to determine the seating arrangement. The intent was to encourage students to work with new classmates rather than sit next to their friends. Waka didn’t agree with the system and often switched seats without permission.

Rather than trying to understand what they were saying in real time, I focused on observing the classroom dynamic.

As an outsider looking in, the room revealed several hidden dynamics. I imagined what it felt like to be a nine-year-old art class student. I pulled out my notepad and began writing down my observations.

A clutter of arts and crafts supplies divided the room into two sections.

The entire back half of the building served as a storage area. Six large industrial sewing machines filled up most of the space. The rest of the area consisted of painting supplies, colorful collages, cardboard cutouts, and a large wash basin for the kids to wash their paintbrushes.

The children were crammed into the front because the entire back half of the room was full. There were 34 children in Waka’s class spread across two columns of nine tables. The screeches of desks, the sound of scissors cutting paper, and children talking amongst themselves collided into an orchestra of sound that bounced off the concrete walls.

The teacher stood in the middle of the runway formed by the tables. She appeared young. Although she couldn’t have been a day over thirty-two, she looked as if the life had been sucked out of her.

I observed her standing surrounded by a sea of children clamoring for attention. Her face, painted in frustration, seemed ready to scream at any moment.

Many children were busy with their projects, cutting, pasting, and coloring faces onto cardboard cutouts. After filling several pages with observations, I rejoined the discussion. Given my lack of Japanese, the best I could do was wait patiently.

The homeroom teacher portrayed Waka as a model student.

She excelled in logic-driven math, reading, and science classes. “Waka always wants to be the first one to get the right answer,” she explained. “Unfortunately, she cannot accept that there is no right or wrong answer in art class. She gets upset that there’s no clear answer.”

I was aware of Waka’s competitive streak. It’s something she’s exhibited since preschool. Waka excelled in math, reading, and science because these subjects have concrete applications of mental models. There is a right or wrong answer. Art is abstract, and right or wrong is a matter of subjective opinion. Waka needs a more definitive gauge to measure what success looks like.

“Optimizers focus on emerging with a single optimum or best answer (Basadur & Gelade, 2003, p. 31).”

Creating this gauge meant she had many questions the teacher didn’t have time to answer, considering the volume of students demanding support.

Observing in real-time, I saw a pattern forming.

The behavioral pattern went something like this: The teacher presents an assignment. Something about the instructions isn’t clear to Waka. She needs help understanding, but she doesn’t want to seem like she doesn’t get it. When the teacher asks if there are any questions, she stays silent.

She sits in her seat, growing anxious. All the other children are busy creating, while she’s still trying to make sense of the assignment. When she finally musters the courage to ask questions, the teacher is too busy to give her the attention she needs.

All those kids crammed into half a room, busy making noise, making progress, feeding her anxiety. The greater her anxiety, the less she can focus.

Until finally, she boils over.

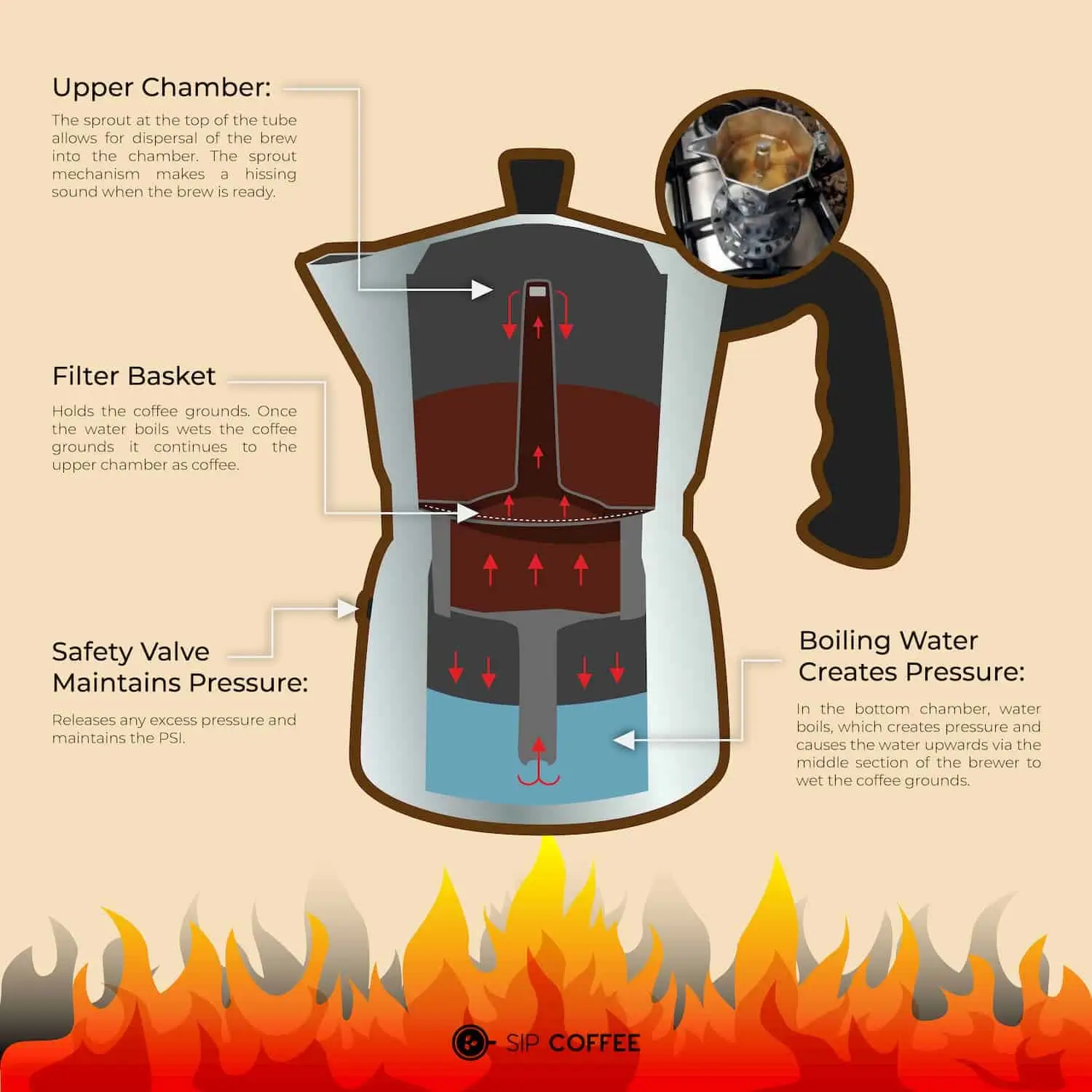

If you’ve ever used a Moka pot stove-top coffee maker, you know what I mean.

First, add the correct amount of water to the lower chamber. Next, add fresh ground coffee to the filter funnel. Screw down the upper chamber until tight. Finally, set the stove-top burner to medium-low heat.

If the heat’s too low, the water won’t vaporize and create enough pressure to push the coffee out of the chamber. Too much heat, and the steam can’t escape fast enough, causing the water to boil over and burn the coffee.

Waka’s emotions boiled over when she didn’t understand the class assignment and couldn’t get the attention she needed. Because the assignments were thrust upon her without advanced notice, Waka found herself in the throes of a creative problem-solving dynamic.

People’s identity changes depending on the environmental factors at play. In math and science classes, Waka saw herself as a top performer who competes to get the right answer first. In art class, she was a confused student, struggling to complete the assignment.

“Depending on who I am, my definition of what is ‘out there’ will also change (Weick, 1995, p. 20).”

Her competitive personality (identity) left her unable to ask for help from classmates she didn’t fully trust. This compelled her to switch seats so she could sit next to friends with whom she could share her vulnerability without feeling judged.

“Controlled intentional sensemaking is triggered by a failure to confirm one’s self (Weick, 1995, p. 23).”

The teacher, overwhelmed by the chaos of handling multiple students, saw Waka as a “rule breaker” who couldn’t conform to the natural order. With nowhere to turn for answers and feeling the pressure to perform, she lashed out at the other students. Waka felt rushed, and her natural desire for understanding went unfulfilled.

“The problem is that there are too many meanings, not too few. The problem faced by the sensemaker is one of equivocality, not one of uncertainty. The problem is confusion, not ignorance (Weick, 1995, p. 27).”

One of the mental models I use is called the Creative Problem Solving Profile (CPSP) inventory. The Inventory measures a person’s unique blend of preferences across the four stages of the innovation process: generating, conceptualizing, optimizing, and implementing.

After evaluating the situation, I understood that the typical art class assignments were highly generative, meaning students were expected to create from a position of ambiguity, explore possibilities without clear guidelines, and be comfortable in not knowing what the “right” answer looked like.

Waka thrives on concrete tasks where the problem is well-defined, success criteria are clear, and she can systematically work towards a “best” solution. She prefers to work with well-defined plans that let her evaluate options against specific criteria before committing to action.

The key difference is that generators (like me) thrive in ambiguous situations with many possibilities, while optimizers (like Waka) require structure and clear evaluation criteria. People like Waka generally fit into the “Optimizer” category according to the CPSP.

“Optimizers combine the preference for learning theoretically with the preference for evaluating options” (Basadur & Gelade, 2003, p. 31).

However, in this situation, Waka was asked to perform generative tasks. She was supposed to be creating from scratch, exploring without guidelines, but her brain tried to make sense of the situation without structure or clearly defined criteria.

This mismatch created the perfect storm I was witnessing.

The Solution

Standing there, taking notes and watching the chaos unfold, I finally had enough information to make sense of the situation.

I drew a model of the situation using the creative problem-solving process and explained to the homeroom teacher how the environmental factors made the situation worse. I described how the cramped room was contributing to the chaos.

The simple solution involved clearing the clutter to give the children more space to work with.

The homeroom teacher sucked on her teeth gently and cupped her chin with her hand. I’m no body language expert, but I’ve seen this pattern enough times to know it meant she couldn’t make that decision.

She explained that the room was so cluttered with equipment because it served multiple purposes. Students of various age groups used it for their projects, e.g., the industrial sewing machines. Clearing out all those artifacts because one student wasn’t conforming to the rules wasn’t an option.

“If we can’t change the room, what if we change the process?” I asked. We needed to develop a procedure that Waka could rely on to get started.

Waka’s struggles seemed to come from feeling rushed to complete an assignment without first having clarity. If the teacher gave her the following day’s assignment at the end of class, she could take it home to develop a plan.

Waka could also come in a few minutes before class started to review the plan with the teacher. This allowed her to ask clarification questions without disrupting the other children. This gave Waka the tools she needed to succeed: advanced preparation and clear structure.

The homeroom teacher thought for a moment and said, “We hadn’t thought of that as an option. Let’s give it a try!”

Waka’s mom was stunned.

She couldn’t believe the teacher accepted my premise. We went from the room is the problem as a ridiculous suggestion, to creating a plan that addressed Waka’s challenges.

The Results

The next few weeks unfolded without much progress. Each day, Waka came home and I’d ask if the teacher had given her tomorrow’s assignment. Each day, the answer was the same. “No,” she’d throw her bag on the floor, annoyed I’d asked.

After about two weeks, the next day’s assignments started rolling in. Waka would sit at the kitchen table, working alone to review the assignment and decide how she’d tackle it the next day.

Before long, word got back that the plan was working. Waka’s behavior changed completely. She was so confident in her understanding of the assignment that she began helping the other children. Her attitude adjustment even earned her the position of teacher’s helper.

The Lesson

Even after nearly eighteen months, I’m still thinking about this experience. On the surface, issues like this can seem like isolated incidents.

The more research I do on the role environmental aspects play on our identities, the actions we take, and how we create our environments, I’ve become convinced that simple dynamics can explain far more complex behavioral patterns than we realize.

As I was wrapping up this article, I ran into a colleague who had recently retired from Ernst & Young (EY) Japan. He’d seen me working in the lounge.

“What were you working on?” he asked. I explained that I was writing this very article and began to introduce the topic briefly.

Before I could even describe the seating arrangement component, he let out a sigh and shook his head.

“You know that reminds me of something they did at EY. They changed the layout to an open office plan to encourage spontaneous conversations between people who don’t normally work together.

Well, it had the opposite effect. No one had an assigned seat, so you never knew where the people you needed to talk to were, and that was incredibly frustrating.”

Same pattern, different environment. EY tried to force creative collaboration by removing structure. Instead of improving idea flow, people spent time hunting for colleagues, creating anxiety instead of innovation.

They’d inadvertently designed an optimizer’s worst nightmare. No assigned seats, no predictable patterns, no way to systematically find who you need when you need them. Just like Waka in art class, employees were drowning in a sea of ambiguity when they needed concrete anchors.

References

Basadur, M., & Gelade, G. (2003). Using the Creative Problem Solving Profile (CPSP) for Diagnosing and Solving Real-World Problems. Emergence, 5(3), 22–47. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327000em0503_5

Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations. Sage Publications.