What Nobody Tells You About Inheriting a Dysfunctional Team

Why your natural instinct to get everyone in a room together is dead wrong.

Key Takeaways

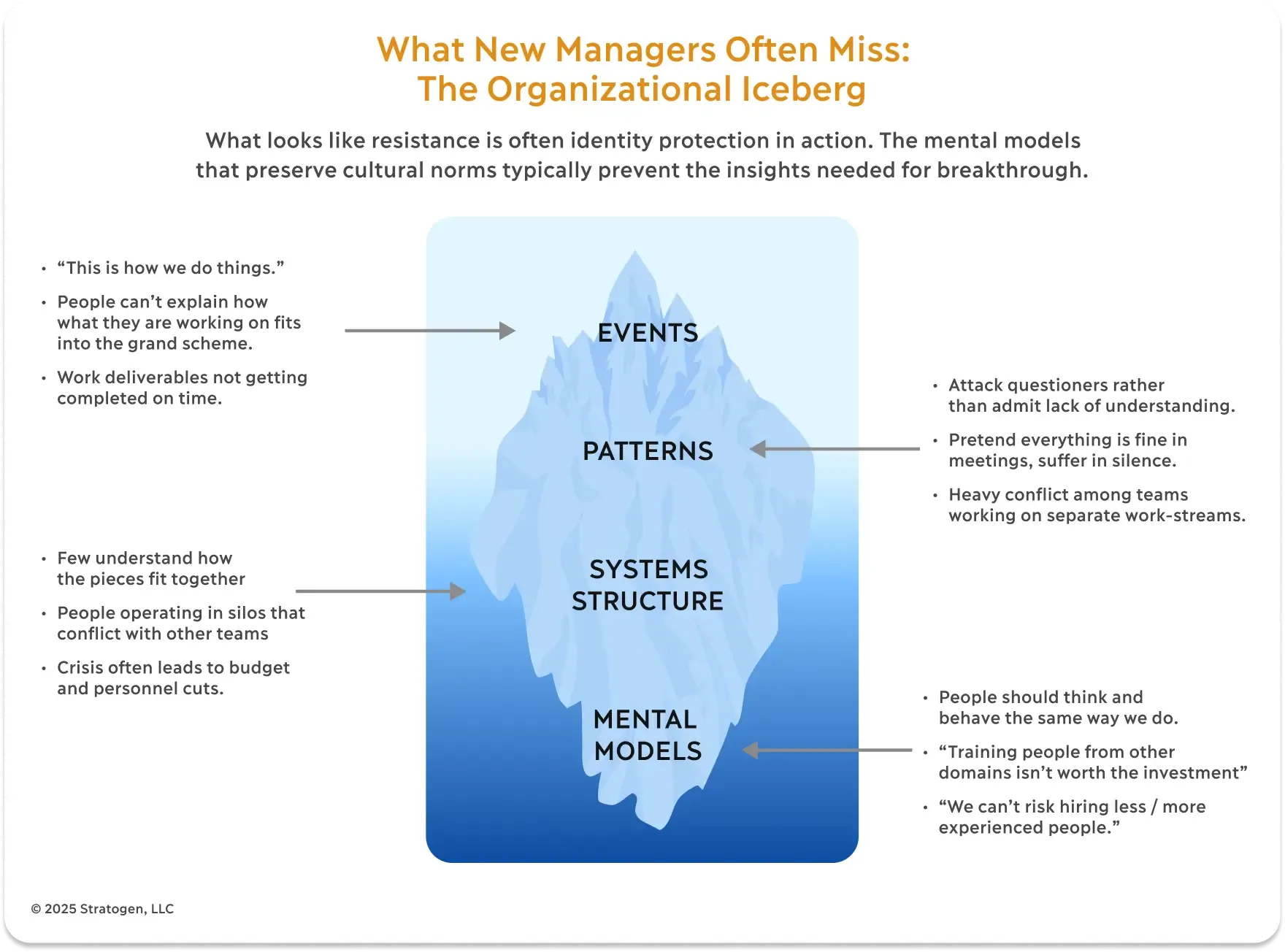

- The Hidden Pattern: When professional identity feels threatened, people pretend rather than admit confusion

- The Strategic Question: “How are they suffering, and how can I help?” reveals more than “What’s everyone working on?”

- The Reconnaissance Method: Map the human terrain through individual conversations before attempting any group work

Mike was choking on his Fruit Loops when I heard him jump up from his cubicle. Pieces of wet cereal were stuck to the corners of his mouth as milk spilled onto the floor. “Go away asshole! What the hell is wrong with you? His program just got canceled, and he doesn’t need you over here harassing him.”

Dennis had just strolled over to my cubicle to deliver an unsolicited opinion about my role in the company. “They should never have hired you. We don’t need another program manager. Things were running just fine here without you,” he said casually.

Less than three weeks into my new job, I was being told to leave. To make matters worse, the government put the program I was hired to manage on hold due to budget constraints.

Once the shouting match ended, I sat at my cubicle wondering if I’d made a terrible mistake. But the real mistake happened three weeks earlier; I just didn’t know it yet.

The Day the Music Stopped

The real trouble started three weeks earlier. What should have been a routine first day turned into a lesson on understanding people.

I’d moved to Los Angeles to begin a new role as a program manager. The company was developing the command and data handling system for the Falcon Hypersonic Technology Vehicle (HTV-2). I’d worked in systems integration and manufacturing, but this was my first major engineering development program. I wasn’t completely green, but I had a lot to learn about the nuances of managing engineers.

On my first day, I arrived at 8 a.m. sharp. The lobby was a ghost town, and I wasn’t getting into the secured facility without a key card. I waited anxiously for nearly thirty minutes until someone finally let me in.

I headed straight for Paul’s office. When I arrived, he was on the phone and motioned for me to sit down. After wrapping up his call, I asked, “Where does Victor sit?”

“Oh, about that. Victor is no longer with us. His last day was Friday.”

That seemed odd. Victor was the COO who had hired me. No, more than odd, it was downright alarming. Paul assured me this wouldn’t affect my standing, so I didn’t pry for details.

“Let me introduce you to the people in the office.” Meeting colleagues for the first time is always a crap shoot. Some people are glad help has finally arrived, and others are cautious of change. You never really know what you’re walking into.

After the introductions, Paul took me to my cubicle. “Wait here, and I’ll get IT to set you up.”

I sat at my cubicle waiting for IT to set up my PC. Once ready, I dove into familiarizing myself with the project.

For the rest of the morning, I pieced together enough information to have a basic understanding. As I worked through the specifications, several questions surrounding system components popped up. Understanding the bigger picture meant I needed the technical diagrams and the bill of materials (BOM).

I walked over to Paul’s office to ask where to get this information.

“Oh yeah,” Paul smiled. “About that. You should probably go over and introduce yourself to the engineering team. They can give you what you’re looking for. You’ll have to go to the Oakdale building, a few blocks away. Here’s the address.”

Paul didn’t offer to accompany me to meet the team. That should have sounded alarm bells in my mind. Not knowing any better, I marched over with my notebook in hand and a three-ring binder containing the statement of work (SOW), technical specifications, and key project milestones.

The Meeting That Changed Everything

When I arrived, several of the engineers were working in their cubicles. Robert, the recently promoted Director of Engineering for the Space Business Unit, suggested I meet everyone at the weekly team meeting.

The guys shuffled into the room, holding notebooks and talking amongst themselves. All were senior-level engineers, several nearing retirement.

They kept glancing at each other, then at me.

I tried to get right down to business after some small talk. “What’s everyone working on?”

Dennis, one of the electrical engineers, shot back, “You’re the program manager. Aren’t you supposed to be telling us what to do?”

My natural defense mechanism kicked in, “How am I supposed to know? It’s my first day.”

The room went quiet. A few engineers muttered apologies for Dennis’s attitude. But something else was happening that I didn’t understand yet.

Robert finally explained: “Look, each week we all get assigned to complete specific tasks. Make a block diagram, review a components list for modifications, and collect test data to prepare a summary. None of us were involved in the proposal work for the program. We have an idea what needs to be done, but who knows what’s involved until we dive into the requirements.” He stretched his hands on the table and shrugged.

The DJ Taskmaster

Over the next few weeks, I pieced together what the shrug meant. Victor had managed the team like a DJ mixing tracks. Each week, he sent emails assigning tasks across multiple programs. The engineers created individual “sound bytes”—such as BOM updates, test procedures, block diagrams, or fabrication drawings — in isolation. The final mix pattern lived in Victor’s head.

At the end of the week, he combined these samples into a unified track that only made sense when assembled.

This DJ system wasn’t because the engineers were incompetent. Years of budget cuts meant the company couldn’t afford specialists sitting on single programs. Victor hired experienced generalists who could jump between projects. The same engineer might touch three or four programs each week, with Victor weaving it all together.

Dennis couldn’t tell me what he was working on because he didn’t know how his pieces fit into the whole composition. Neither did anyone else. But admitting that meant confessing that he, a senior engineer with decades of experience, was simply submitting tasks blindly.

Instead of admitting this workflow dynamic, Dennis tried to turn the tables on me. The team had lost their conductor without warning. On Friday, Victor was mixing their tracks, and on Monday, silence. No wonder they were anxious, angry at the lack of notice, and worried about their future. And here I was, asking them to play me a song they’d never even heard.

Each team member handled the chaos differently.

Robert’s Warning

Robert handled his confusion by warning me away. One afternoon, we were discussing how one of the processing systems worked. I sat listening and taking notes. Then Robert casually planted the seed that I wouldn’t last long.

“Look, this probably isn’t going to work. Victor shouldn’t have hired you. We need someone with more experience. All of us have been in the business for decades, and you’re just not there. Let’s try to work together for whatever amount of time we have, but don’t get your hopes up.” He kept drawing on the whiteboard like a professor lecturing a student about his declining grades before class had even started.

I bit my tongue because Robert wasn’t trying to be malicious. His words reflected the organizational culture that believed the company should only hire senior professionals. Investing in less experienced talent was a waste of resources.

The Breaking Point

The following week, while delivering a budget update to Paul’s office, the CEO rushed into the room, waving his arms and complaining about Robert. “He’s not doing anything. What is this? The engineers are all over the place. None of the proposals are getting done. Even the time cards haven’t been turned in yet for accounting. They’re just sitting there on his desk. This guy, he’s not going to make it in this new role. He should go back to engineering.”

Part of me wanted to revel in hearing this new information.

Strutting past Robert’s office, I saw him sitting at his desk in a puddle of confusion. Stacks of boxes lined the walls of his new office. Piles of paper covered his conference table. He sat slumped in his chair, staring out the window.

I bolted through the doorway, and he snapped to attention. “Well hello, how’s Roy doing today?”

I closed the door and barked at him, “You’re not getting your work done. Your boss is complaining about you, and if you don’t start making progress, you’re going to be in a bind. You can keep on putting up this front if you want, or you can let me help you.”

He leaned back and sighed. “Is it that obvious?”

“Yes,” I said affirmingly. “You can either work with me, or I can watch you fail. I can see all the engineering time cards sitting on your desk. Hand them over, and I’ll take care of them going forward for you. I’ll go review them with the engineers, and you can sign off once I’ve validated them.”

“Okay, here you go.” He said in relief. Robert served in the Navy during the Vietnam War. He wasn’t interested in training a new program manager. He needed a command and control management approach to help him transition into his new role. Something that my background serving in the Marines was ideally suited for.

Over the coming months, Robert and I figured out how to work together. He had the knowledge gained from years of working in the trenches of processor and hardware design that I didn’t have. I brought the aggressively helpful energy and wherewithal to serve as his enforcer and administrative arm. This allowed his technical expertise to shine without getting bogged down in management minutiae.

Dennis’s Breakdown

Dennis’s situation required a different approach. For the next few months, his hostility only intensified, no matter how hard I tried to bridge the gap. It wasn’t just me who noticed; his attitude spilled over into other relationships across the organization.

Finally, after I’d had enough, I called him into my office and closed the door. Instead of confronting his behavior, I asked him a simple question out of frustration:

“Is everything okay with you?”

He seemed startled. “What do you mean?”

“Do you need help? You seem to be struggling with something.”

The mask he’d been wearing finally cracked. Dennis confided that he was struggling with serious issues at home. The chaos at work had thrown his entire world into disarray. What I saw as a new beginning, Dennis saw as the beginning of the end. Everything in his life was falling apart, and he was barely holding on.

He broke down in my office, and I sat with him, listening to his story. As he walked out that day, he looked back and said, “You’re the first person in a long time who cared enough to ask me about my problems.”

Unfortunately, Dennis’s defensive behavior had already damaged his standing in the company, and he was let go a few days later.

The Lesson They Don’t Teach You In Business School

Looking back on that first team meeting, I finally appreciate what I’d missed. When Dennis challenged me, “Aren’t you the program manager? Why don’t you tell us what we’re supposed to be doing?” he wasn’t questioning my competence.

He was protecting himself. Here was a senior engineer with decades of experience who couldn’t explain what he was working on.

Admitting that would mean confessing that he was operating on autopilot with Victor serving as his taskmaster. So, instead, he attacked me. In his mind, it was better to challenge the new guy than reveal his confusion.

Robert did the same thing, only differently. Telling me I wouldn’t last deflected his own sense of failure. It’s like someone who’s drowning, tossing their life preserver to someone who just got into the water.

Both men were scrambling to protect their professional identity. Yet, this complex dynamic was invisible to me then; I only saw resistance where I should have seen fear and anxiety.

This is the trap that almost every project manager walks into. You show up with your notebooks and frameworks, ready to map out the workflows and system dynamics.

But at this stage, the workflows aren’t the problem.

The people protecting their sense of professional self. That’s what determines whether you succeed or fail.

The standard playbook tells you to get everyone into a room to bring you up to speed. This includes collecting everyone’s thoughts and ideas, mapping them out, and planning a new path forward.

However, you need to lay the groundwork before you even consider organizing a team meeting or workshop. This means investing time to understand the key players and organizational dynamics involved.

Otherwise, you’re likely to wind up witnessing organizational theater where some people feel threatened, and others put on a performance.

Here’s what I was actually dealing with, and what most new managers never see:

The Strategic Question Nobody Asks

If I could go back to that first day, I’d do a lot of things differently. Instead of marching into that conference room and asking, “What’s everyone working on?” I’d start with individual conversations. Not conversations about processes or workflows, but about people. Their backgrounds, their concerns, what they’re good at, what worries them about the changes ahead.

In most organizations, people don’t suffer openly; they hide it behind professional masks. As Joe Polish puts it, the key question to answer is: “How are they suffering, and how can I help?”

After each conversation, I’d build a different kind of map. Not of technical systems, but of the human terrain. Who’s overwhelmed like Robert? Who’s defending territory like Dennis? Where are the real expertise gaps versus perceived ones?

Polish calls this being a “pain detective.” It means staying aware of people’s emotions, wanting to learn their stories, and connecting over shared challenges. This isn’t just preparation for process improvement. It’s an organizational reconnaissance mission that determines whether your efforts succeed or fail.

Once you understand the atmospheric conditions of everyone’s work life, you can discover the identities they protect, the fears they won’t share publicly, and the confusion they hide. Then you can address those concerns directly.

Sometimes that means barking orders at a Navy vet who needs structure. Sometimes it means asking a hostile engineer if he’s okay. But it always means seeing past the performance to understand how they’re suffering and how you can help.

The real work of process improvement isn’t drawing workflows. It’s understanding the people inside them well enough to help them drop their masks.

But how exactly do you map the human terrain? What questions reveal what people won’t say directly? That systematic approach to reading organizations is where we’ll go in the next article.

P.S. If this article resonated with you, you probably know someone facing their own Dennis or Robert. Feel free to pass it along.